In all the Canadian provinces, farm animals have marginal legal protections. They can only rely on laws that explicitly or implicitly apply the federal Codes of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farm Animals (Codes).[1] The Codes are developed and administered by the National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC).

Any action pertaining to farm animals is immune from prosecution if it qualifies as standard operating procedure within the industry, outlined in the Codes. Below are a just a few examples of accepted industry practices per the Codes, which the NFACC paradoxically considers both humane and painful:

- Cattle: Branding, disbudding, dehorning, gunshshot to the head (to render the animal unconscious).

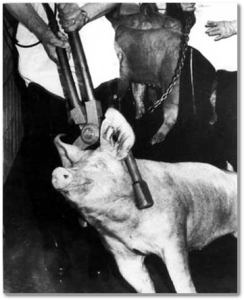

- Pigs: ear notching, ear tattoing, tail-docking, teeth-clipping, castration cause pain and distress, pregnant sows rendered immobile in tiny crates, penetrating captive bolt and gunshot to the head (to render the animal unconscious).

- Veal calves; liquid diet, caged in tiny veal crates, gunshshot to the head (to render the animal unconscious).

- Chicks (non-saleable): high-speed maceration.

- Chickens: beak trimming.

- Spent egg-laying hens: blow to the head by means of a penetrating or non-penetrating mechanical device (to render the animal unconscious).

- Rabbits: decapitation.

Eight provinces have incorporated in their animal protection legislation, the Codes, thus legally requiring minimum acceptable standards for farm animals.

Eight provinces have incorporated in their animal protection legislation, the Codes, thus legally requiring minimum acceptable standards for farm animals.

Section 4 of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Animal Protection Standards Regulations follow NFACC’s Codes.

Section 4 of Prince Edward Island’s Animal Protection Regulations also specifically follow the Codes.

Section 3 of Saskatchewan’s Animal Protection Act provides that an animal is not considered to be in distress for the purpose of establishing an animal welfare offence if the animal is handled in a manner consistent with a standard or practice that is prescribed as acceptable. Under Part II of the Animal Protection Regulations, the Codes are deemed to establish the acceptable standards. Thus, an animal welfare offence cannot be established if a producer has complied with the standards in the Codes.

Per section 2 of Manitoba’s Animal Care Regulation, the Codes are “incorporated by reference”. Practices consistent with the Codes are specified as acceptable for the purposes of determining whether an animal welfare violation has been committed under the Manitoba Animal Care Act.

Section 32 of New Brunswick’s. Section 4 of Regulation 2000-4 states that a person cannot be convicted of an offence if their behaviour is consistent with an adopted code of practice; Schedule A adopts NFACC’s recommended Codes. Again, the regulations exclude from prosecution the treatment of farm animals that complies with the Codes.

Generally Accepted Practices

Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, and Ontario exempt “reasonable and generally accepted practices.” [2] Quebec exempts “generally recognized rules.” The Yukon exempts “reasonable and generally accepted practices” that are “carried out in a humane manner.” These terms are not defined in their regulations and enabling statutes.

The Codes comprehensively and meticulously establish recommended and generally accepted industry practices. They serve as criteria in determining if an offence has been committed at the provincial level.

In conclusion, whether they are affirmatively or implicitly included in provincial legislation, the Codes are the nominal protection that farm animals have. Enjoy your steak!

[1] https://www.nfacc.ca/codes-of-practice

[2] Animal Protection Act, RSA 2000, c A-41; Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, RSBC 1996, c 372; Animal Protection Act, SNS 2008, c 33; Ontario Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, RSO 1990, c O.36